This blogpost is based on a talk that a friend (who is a doctor of philosophy) and I (a former philosophy teacher) gave back in 2016, when it seemed to be particularly common for those of us into philosophy to be fielding questions along the lines of “Isn’t philosophy pointless now we have science?”, “What has philosophy given the world compared to science and technology?” and “Isn’t philosophy dead, like jazz or guitar rock?” Having both found ourselves on the wrong end of such frustrating pub conversations – and worse, having seen similar arguments coming from high-profile science champions such as Bill Nye The Science Guy, Neil deGrasse Tyson and even Stephen Hawking (RIP) – we decided it was time to gather up our 'beefs' and air them. Now it’s almost three years later but these 'beefs' bear repeating, so here goes.

In the first instance it’s tempting to take “What has philosophy given the world?” at face value and argue back with “How about all of politics, or ethics, or formal logic... or SCIENCE ITSELF?” but this doesn’t tackle the accusation that philosophy has "served its purpose so can now be retired” and kind of misses a more fundamental issue – that to suggest science could replace philosophy is to fundamentally misunderstand the difference in what science and philosophy respectively do.

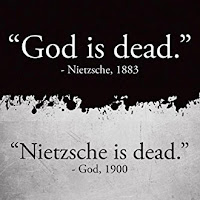

I would be the first to admit that many of the 'classic' philosophical questions and quotations that get trotted out again and again are creaky old obsolete BS (the 'mind/body' split anyone?) – but that kind of undergrad cliché stuff is no more representative of the cutting edge than an apple falling on Newton’s head is of the current state of physics. I would also be the first to admit that that academic philosophy seriously needs to do more to fight the tendency to retreat into an ivory tower of needlessly impenetrable jargon and navel gazing, and needs to engage and communicate with other academic fields and wider society more – but that doesn’t mean philosophy in general is dead and buried.

Bill Nye The Sceince Guy's special journey

Bill Nye’s arc is an interesting one, because in 2016 he posted a video in which he pooh-poohed philosophy as pretty much useless, and not worth bothering with, compared to science.

As Olivia Goldhill in Quartz put it: “The video, which made the entire US philosophy community collectively choke on its morning espresso, is hard to watch, because most of Nye’s statements are wrong. Not just kinda wrong, but deeply, ludicrously wrong... Nye’s remarks, which conflate ideas from completely different areas of philosophy, are a caricature of the common misconception that philosophy is about asking pointlessly ‘deep’ questions, plucking an answer out of thin air, and then drinking some pinot noir and writing a florid essay.”

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry in The Week pointed out: “To argue that philosophy is useless is to do philosophy... More to the point all of the institutions that make modern life possible, very much including experimental science, but also things like free-market capitalism, the welfare state, liberal democracy, human rights, and more, are built on philosophy. All of these things are cultural institutions: They exist because many people find certain ideas valuable and decide to act on that basis... If the ideas that underlie these cultural institutions become lost, or misunderstood, those cultural institutions might malfunction. This is very much the case of science.”

But in 2017 Nye revealed the backlash had led him to a complete about-face on the issue after “months” of sleepless nights as he decided he must learn more about philosophy – and he now believes everyone would benefit from a more 'philosophical' outlook, stating “I’ve come late to this. Now I’m all about the philosophy. Bring it on.”

For those of you baffled at Bill Nye’s new-found enthusiasm, still convinced that science makes philosophy pointless, I urge you to ask yourselves the following:

1) What do you imagine philosophy is?

Because it has such a long and diverse history, and the term has been used in different ways at different times by different peoples, what exactly we mean by 'philosophy' is tricky to pin down. The word itself, of course, derives from ancient Greek: 'philo' meaning love, 'sophos' meaning wisdom – hence, literally, “the love of wisdom”. The Oxford Dictionary definition is: “The study of the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality and existence, especially when considered as an academic discipline.”

For the Greeks, philosophy started as a combination of the semi-mystical with what would later be called 'natural science', with questions such as “What is the universe made of?”; with Plato, Socrates and Aristotle the emphasis shifted to practical and moral questions such as “How should the perfect society be arranged?” and “What is it to live a ‘good’ life?”; the term has been used to cover all manner of religious thought and theology from cultures all over the world, from Middle Eastern mysticism to medieval Christian scholarship to European alchemy to Buddhist spirituality to ancient animism and everything in between; it has been concerned with what exists and what the nature of what exists is; with what we can know and how can we know it; with how language works and how logic works and mathematics works and how such things relate; with the human condition – psychology, consciousness, free will, existence in general and our place in the world; with the study of cultures and cultural criticism, what is actually going on in our society and others and whether that could or should be different... which leads us back to politics and ethics once again.

The above list only scratches the surface but what should be clear is that philosophy is NOT one method, NOT tied to any particular subject, NOT tied to any particular time or culture and NOT tied to a functional end goal or practical application. It is also absolutely NOT just a matter of “what I believe” (Marilyn Monroe quotes, touchy feely platitudes, unquestioning religious or political dogma, random cute 'thinky thoughts' that are not pursued or subjected to any scrutiny). If anything distinguishes philosophy, it is that it is recognizable as rigorous, structured, analytical thought – even if you think that it is misguided or plain wrong. What philosophy is, is a catch-all term for the history of analytical human thought.

Now try asking again: “Isn’t analytical human thought pointless now we have science?”, “What has analytical human thought given the world compared to science and technology?” and “Isn’t analytical human thought dead, like jazz or guitar rock?”... See? You get my point.

2) What do you imagine science to be?

Unlike philosophy, science is a method. There may be multiple schools, stances, methodologies and disciplines within science, but generally speaking, to be identifiable as science, there needs to be an empirical basis to how knowledge is arrived at. A testable theory is drawn up, then tested in some way and accepted, rejected or tweaked depending upon the results... then the theory is developed further for further testing and retesting in a cyclical and continual process of model-building and refinement. The scientific method has certain accepted philosophical underpinnings, though these have been argued over (and continue to be argued over) by theorists and – yes – philosophers, to ensure that how we do science is as rigorous as it can be, and that we can be as sure as we can be that what we are gathering from the process (and how we interpret what we have gathered) is as valid and reliable as it can be.

But science is not as united as the layman thinks – all fields tend to be deeply divided by rival schools with different outlooks competing for supremacy; much of what is taken as 'hard fact' by the layman (because a man in a white coat said it) is not taken that way in the academic field – there is a lot of uncertainty, theorising and 'best fit' interpretation going on with a only a relatively small core of undisputed 'fact'. Furthermore, the facts themselves do not tell us what meaning we should take from them: interpretation and meaning is put on by us afterwards, in applying how the facts relate to us and what relevance they appear to have to our current lives, given our other knowledge – other knowledge which in turn is filtered by interpretation.

This means that when scientists start banging on about the 'meaning of life' or the 'ultimate truth', they are leaping beyond what science is supposed to be about or equipped to do and in fact engaging in (often pretty amateurish) philosophy. Please do not confuse pseudo-philosophical bluster by scientists with actual science – it's perfectly possible for a researcher to do perfectly good, solid science and then gush a bunch of shoddily-thought-out philosophy around it, without even really being aware that they're doing it; because they haven't bothered to even glance at the fruits of thousands of years of rigorous, rational, analytical thought that has thoroughly mapped the problems and pitfalls of certain arguments and ways of thinking because “Isn’t philosophy pointless now we have science?” I mean, FFS.

3) Do you think it's pointless to be self-aware about the way we think and the concepts we use?

If philosophy was only about discovering 'objective facts' about the objective world, then – Yes! – science does that much better. But even the most dry, 'objectively' framed science is riddled with everyday assumptions and concepts that are virtually never analysed outside of philosophy. As every philosopher knows, even our most basic concepts – about life and existence, space and time and number and identity and logic and knowledge and consciousness and cause and effect and everything else – often start to unravel on scrutiny, proving to be much more complex than assumed, as elusive as trying to catch a cloud, or simply liable to fall apart all together. These concepts underpin everything about the human condition, the human world, the human experience – and are the product of 'us' in relation to the 'world'. As such thinking and talking about them is a perfectly valid way to unpick and analyse them, for greater understanding. The focus of philosophy is not simply on pinning down objective facts – rather it is about analysing the very concepts that make up how we engage, experience and interact with the world and others. Philosophy is about humanity’s self-awareness.

As put by Cambridge don Raymond Geuss in his recent alternative history of philosophy Changing the Subject: Philosophy from Socrates to Adorno: “Confronted by a standard question arising from a normal way of viewing the world, a philosopher may reply that the question is misguided, that to continue asking it is, at the extreme, to get trapped in a delusive hall of mirrors.” One of the most characteristic things about philosophy is that it questions the questions, which may seem infuriating but is actually the unique strength of it – it never takes things at face value, always analyses the underlying assumptions and attempts to bypass or overhaul conventional ways of thinking, to find new ways to look at old and entrenched problems, or explore a deeper, more fundamental understanding of the concepts involved.

This is best illustrated by the fact that, the deeper you go into philosophy, the more 'meta' the questions get. You may start off asking whether, for example, abortion is morally justified or morally wrong; then you move to asking if you can logically 'think out' morality, and come up with a system that will tell you whether any particular moral question (e.g. concerning abortion) is right or wrong; then, when you get really 'hard-core', you start asking what the concept of morality even is, where it comes from, what it’s based on, how it functions and plays out in the world. These are different levels of thinking and arguing – and notice the more 'hard-core' philosophical questions get, the less 'practical' they are. The impracticality of philosophy is something I will vigorously defend – philosophy at its most fundamental should be free and abstract, removed from the pressures of having a particular purpose. Just like art, having a particular functional goal (for example to push a political idea, sell a product or appeal to the tastes of a particular demographic) tends to limit, warp and bias the results. Philosophy, like art, is defined by being removed from practical concerns – in fact a focus on practicality can undermine it.

It’s about the journey, man, YOLO

Philosophy and science are not two rivals both racing to get to the 'facts' on the same racetrack – with science the younger, fitter, better equipped competitor. They’re not on the same racetrack at all; they are different beasts in different games. And yet they are inextricably linked. Philosophy not only begat science but is weaved throughout its methods and theorising today in ways that still need to be regularly unpicked and paid attention to keep the engine of science well tuned (It should also be noted that both are also bound up with a third Siamese twin – the realm of mathematics, statistics and logic).

It’s about the journey, man, YOLO

Philosophy and science are not two rivals both racing to get to the 'facts' on the same racetrack – with science the younger, fitter, better equipped competitor. They’re not on the same racetrack at all; they are different beasts in different games. And yet they are inextricably linked. Philosophy not only begat science but is weaved throughout its methods and theorising today in ways that still need to be regularly unpicked and paid attention to keep the engine of science well tuned (It should also be noted that both are also bound up with a third Siamese twin – the realm of mathematics, statistics and logic).

Certainly, you rarely get a 'right' answer in philosophy, but you can certainly uncover 'wrong' – ie. arguments that simply don’t work, concepts that are inadequate or flawed, and scientists really should pay attention to this before going beyond the data and espousing wider metaphysical theories and interpretations about life and the universe and everything. Philosophy, though, is really not just about bagging a fact as an end result, it's about the journey: the deeper understanding gained by analysing and unpicking the concepts we use and assumptions we make – it is about the structure of our thought and the world as we experience it.

But the lack of a particular, practical end goal does not make philosophy pointless. Think about it: If you say hard-core philosophical questions are pointless to think about, you are essentially saying it’s pointless for individuals, societies, cultures – or even humanity as a whole – to be self-aware.